Between challenges and opportunities, let's talk about climate finance

As humans, we are in a race against time to stop environmental degradation and climate change. Modern human activity has generated an enormous imbalance. Billions of tons of greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere year after year, and the numbers continue to rise; ecosystem loss and soil degradation hinder natural carbon sequestration processes and threaten our planet's biodiversity.

Within the framework of the Paris Agreement, the objective was to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels - considering that today we are already 1 degree Celsius above. However, if substantial reductions are not achieved in the short term, an increase of 3 degrees Celsius or more is expected by 2100 (Arnell, 2021), which will cause irreversible damage to ecosystems, biodiversity, the climate system and human life forms.

Problems of food and water insecurity, migratory pressures and increased poverty, increased conflicts, millions of dollars lost in public and private infrastructure, among other economic and social disruptions, will be - and already are - our daily lives. However, there is still time to slow down the path we are on; the challenge is enormous and requires a profound transformation in the way in which we generate energy, produce goods and services, and channel economic resources into ideas and projects that build the world.

How much does it cost to resolve the crisis we are experiencing?

The United Nations describes the climate crisis as a challenge of 1 trillion dollars by 2030 (United Nations Organization, 2021). This estimate is based on investment commitments made by “developed” nations with the objective of channeling resources equivalent to $100 billion annually to “developing” nations and thus investing in solutions for mitigation and adaptation to the crisis. However, it is clear that this is a symbolic amount rather than ideal and that it is necessary to mobilize many more economic resources in order to limit the planet's temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Morgan Stanley, a multinational investment bank, estimates an investment need of 50 trillion dollars by 2050 (Klebnikov, 2019), that is, on average 1.7 trillion annually just to finance the energy transition. For its part, the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimates that to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis, an average investment of 4.3 trillion dollars per year is required by 2030 (Naran et al., 2022).

Achieving a credible transition towards the decarbonization of the economy in this decade then requires trillions of pesos invested annually in initiatives that promote climate mitigation and adaptation on the planet; however, it goes beyond that alone, since this increase must be accompanied by a substantial decrease in investments aimed at projects with a high impact on greenhouse gas emissions, something that does not end up happening today.

We are talking about such a radical transformation, that none of these actors can carry it out on their own.

Who is funding climate action?

The public sector, made up of governmental and intergovernmental entities, is the main funder, representing 51% of the total resources allocated to climate in 2020. The other half is a mix of private actors; corporations account for about 20% of the total, and financial institutions - both banking and private investment - together represent another 20%. The remaining 9% are individuals and households.

Most of these resources, both public and private, have been channeled to projects in the form of loans -61% of the total, which have generally been placed at market prices. 33% has been invested as shareholding in projects and companies, mainly by corporations and independent actors.

The remaining 6% has been given as donations, almost entirely by the public sector. This explains why most of the economic resources - 90% - are being allocated to mitigation projects and only 10% to adaptation projects.

How are we doing?

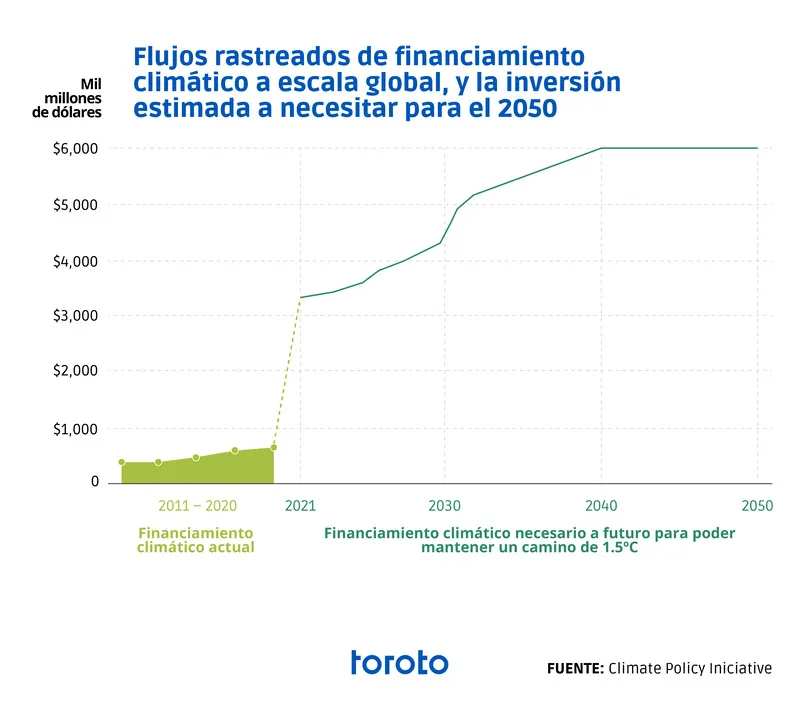

Climate investment doubled in the past decade, reaching a cumulative amount of $4.8 trillion between 2011 and 2020. This represented a Average annual increase of 7%, reaching $632 billion in 2020 and $850 billion in 2021, according to ICC estimates. This means that, despite a clear upward trend, the amount of annual investment must still grow 590% if we want to reach the goal set for 2030, that is, we are facing a gap of 3.5 trillion dollars per year. (Naran et al., 2022). We still have a lot to do.

Diagram 1. Estimated annual climate finance for 2050

In general, we can say that there are some operational difficulties in climate finance. First, there is a long understanding curve on how to evaluate these opportunities for climate action and clearly measure the economic benefits they generate.

Second, there is a gap in the timing of climate projects and the time in which private investors, especially financial actors, expect to earn returns. The “long terms” between the two are usually several years apart.

Finally, there is general ignorance and possibly a lack of standardization in how to measure the quality of a climate project, which often causes the allocation of resources to generate very few real benefits.

Can the public sector finance the fight against this crisis?

To consider that the mobilization of public sector resources alone can reduce the funding gap and generate the expected impact on climate goals is unrealistic and highly complex.

First, by its nature, the public sector lacks the speed required by this challenge. If we consider as an example the commitment to mobilize 100 billion dollars from “developed” nations to “developing” nations within the framework of the United Nations Organization, we see a very clear non-compliance and an enormous difficulty in the appropriate mechanisms to mobilize these resources, not only to the countries that need it most, but also to quality projects that address the challenges of climate adaptation.

Second, the participation of the private sector is mandatory, not only to reduce the funding gap, but to achieve the transformation of the energy, productive and financial system. This means that in order to credibly speak of a decarbonized economy, a comprehensive approach between these sectors is required. We are talking about such a radical transformation, that none of these actors can carry it out on their own.

It is essential that supply chains migrate from an operating logic to a regenerative approach and that the energy system transitions to clean sources. In these objectives, large corporations lead the way because they are responsible for most of the greenhouse gas emissions currently accumulated in the atmosphere (Ritchie and Roser, 2021), therefore, they have in their hands not only a responsibility for repair, but also the possibility of generating the greatest reduction effects, given that since they are the main emitters at present, their actions have impacts that can really move the scales in the future.

To meet this challenge, it will be essential that the economic resources that flow through the channels of the financial system end up in projects, organizations, companies and initiatives that are consistent with this transformation. In addition, the public sector must create appropriate incentives to promote a faster transition and establish clear rules and transparency mechanisms that promote quality initiatives.

Finally, how should we think about climate finance to achieve global and common objectives?

We are still far from being on the right track to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis.

It is essential to channel more and better funding towards these objectives, to reduce economic resources that are allocated to “dirty investments” and to achieve more ambitious and serious commitments on the part of governments, the financial sector and corporations, which will lead them to a profound and fundamental change in the way in which we manage and relate to our natural resources.

There is no solution that excludes one of these actors; or one that is resolved taking into account a single sector. We all need to find articulated ways to transform the way we exist, hand in hand with conserving, protecting and restoring the ecosystems that we have left and that are in serious danger. Intersectoriality will always be the best possible practice. How to think about climate finance? As a tool of the utmost importance, of enormous scope, of urgent need that can only be managed correctly if we involve those who must and can really solve the climate crisis.

About the author:

Alejandra is Director of Finance at Toroto. She graduated from International Business and is currently pursuing a master's degree in Finance. One of the things she enjoys most is learning about nature and its relationship with the economic system; for her it is incredible to put her energy into a project that seeks to generate a large scale impact.

Bibliography:

Explore reflections, research and field learning from our work in ecosystem restoration.