Institutions matter: mining, conflict and violence

A year ago, in April of 2020, Adan Vez Lira was murdered, environmental activist in Veracruz. In recent years, he had dedicated himself to opposing open-pit mining projects given their socio-environmental impact on nature reserves. The incident is part of 7% of attacks on environmental activists attributed to mining (CEMDA 2021). There are many stories like this where extractive activity has been at the heart of the development of violence. Different forces and dynamics have played their part in these conflicts: the socio-environmental impact, failed negotiation processes, the asymmetries of power between company, state and community, among others. However, the role of institutions is key to understanding why it became a violent conflict. Agrarian and Mining laws, the lack of effective dispute resolution mechanisms, the lack of just state institutions for the defense of the territory, institutionalized impunity in justice mechanisms, etc. All these institutional aspects, in the end, played a role. In this article, we precisely want to explore how institutions, formal and informal, have been key to understanding the violent conflict surrounding mining projects in Mexico.

Mining itself has a particularly disruptive socio-environmental impact. In addition, the vast majority of mining concessions are located in ejidal, communal or indigenous territory. These territories, for the most part, constitute communities with limited power vis-à-vis transnational corporations in negotiation processes. Here conflicts arise, which can arise from very survival (exploiting my territory implies the destruction of their livelihoods) to the clash of conceptions of the world, where the exploitation of nature is not acceptable within communities. Violence, then, emerges when institutional frameworks do not privilege the resolution of conflicts in a just manner, but rather reinforce the asymmetries of power between actors.

Before I dive headlong into the institutional discussion, it's important to understand why extractive activity gives rise to conflicts. There are a wide variety of studies that focus on explaining the origin of these conflicts. It is a topic not only of high academic interest, but also of political and economic interest. Strategies for state economic development, monopolization of sectors, struggle for territorial autonomy and many other sociopolitical trends emerge from this activity. The Mining Chamber of Mexico registered 169 projects stopped due to mining conflicts around the country between 2013 and 2018 (Sol, 2020). But I want to focus on three explanations of the origins of conflicts surrounding extractivism: survival, belief and power.

La survival is one of the most basic and clear explanations for the origins of conflicts surrounding extractivism. In communities and populations where dependence on the immediate environment, activities as disruptive to the land as mining, can have a direct impact on the livelihoods of the inhabitants. This is where popular mobilizations emerge to defend the territory, which Martínez Allier and Ramachandra Guha call popular environmentalism (2009). These mobilizations are in direct confrontation (not necessarily violent) with mining and similar processes, because they see their presence as an existential threat.

This was explained by the ejidatarios of Benito Juárez when they rejected the mining activity of the Canadian company MAG Silver in 2006. The main argument was that mining activities were going to pollute the Del Carmen River, and a years-long conflict broke out between the company, the ejidal commission and the same residents of the municipality of Buenaventura (where the ejido is located) who worked for the mining company. This conflict culminated in the murder of a couple who were members of the agrarian organization El Barzón, Ismael Solorio and Marta Manuela Solís. Defending the basin is an existential and vital issue for community life, triggering a conflict that has cost lives.

Las beliefs contradictory and competing ontological conceptions of the world are also related to conflicts for survival. In some ways, they are also conflicts that originate from existential threats to communities or peoples. However, they are existential threats to different ways of life. Arturo Escobar describes these conflicts as disputes “over possible or acceptable ways of life” (2014). This is where the differences between understanding the environment as a separate entity from human societies or as an integral part of society itself, for example, come in. Yásnaya Aguilar, an Ayuujk intellectual from the Mixe Region, argues that these are precisely the main differences between Western environmentalism and the defense of the territory of indigenous peoples.

Proof of this has been the defense of the sacred territory of the Comcáac nation in Sonora. Regardless of the illegal mining procedures (initiating extractive activities without the prior consent of the Comcáacs, not having an Environmental Impact Statement, or land use permit from the city council), the conflict stems from the substantial difference between understanding their territory. In addition to being the source of life of the Comcáacs, it is also the territory where their ancestors lie and of which they consider themselves an existential part. For mining, it is a region rich in minerals. The difference is, clearly, the asymmetry of power between the Comcáacs and the mining company.

This is how the power plays its part in detonating conflicts in mineral extraction areas. This dimension is the common thread between the two previous ones, survival and belief. When we talk about power in this context, we are talking about the exercise of power within asymmetric relationships: multinationals allied with the State and communities. Two methods are key to understanding this: the unequal distribution of benefits and the criminalization of protest. In terms of uneven distribution, we talk about the fact that the benefits extracted from mining operations are not necessarily distributed equally either among the community or with the community itself. This causes distancing and damage to intra-community relations. In terms of criminalization, it is the alliance between the State and companies that criminalize protesting these projects as a tactic to delegitimize voices opposing the project.

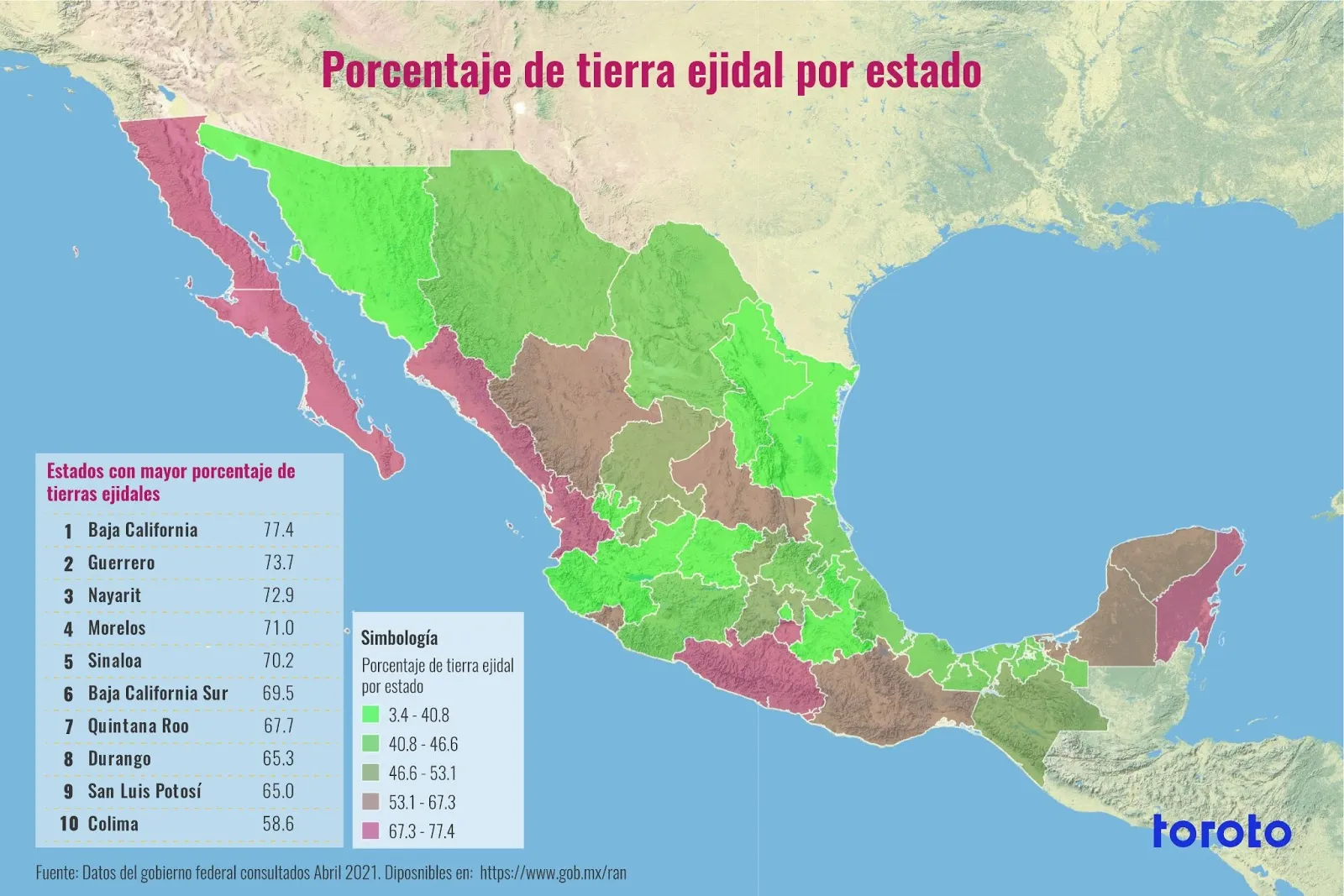

By understanding the origins of the conflicts that exist around mining, we can explore the role of institutional orders in violence in these instances. As I stated before, in this article I refer to institutions not as synonymous with governmental bodies, but as the rules of the game that have been determined formally (such as the Constitution, for example) or informally (such as the famous Fingering presidential of the PRI era). In relation to the violence surrounding mining, I refer to the different rules of the game that incite violence. These rules are manifested as violence as an institutional order, competition between different institutional orders and the violent suppression of local institutions. To explore these three facets, I want to explore land tenure in Mexico, mining concessions, and mining hot spots. To explore this, we are going to focus on the ejidos, a communally owned institution recognized by the Mexican State, where 60% of them have mining projects (Sol 2018:99).

In cases where violence is no exception and has been integrated as a way of organizing society, then when conflicts around mining explode, violence is the way to mediate and resolve these conflicts. The different actors (mining companies, federal and local authorities, social organizations, organized crime) use violent methods as the language that is understood. Given the institutional nature of ejido lands, violence can become a method in which dissenting voices are convinced to obtain the consensus approval of the assembly. In its 2019 report, the Mexican Center for Environmental Law identified a variety of tactics to threaten environmental activists or ejido commissioners who oppose projects.

This is how contradictions between different institutional orders (principles of private property and communal property) can also cause violence. On the one hand, national and international legislation1 protect communal lands, the rights to consultation and the protection of communities from social and environmental harm. On the other hand, there are states like Guerrero (Map 1, 2 & 3) where it has a high percentage of ejidal land and where mining concessions have grown in the last 6 years. These maps paint a case where, without establishing causality, there is a relationship between the growth of mining conflicts (Sol 2019).

1: International Instruments: Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, among others. National Instruments: National Instruments: Agrarian Law, General Law on Human Settlements, Article 27 of the Constitution, among others.

National maps: 1) Ejidal land tenure by state, 2) Mining concessions in 2015, 3) Mining concessions in 2019

So much so, that the most critical cases of institutional imposition can increase the risk of violence even more. The case of indigenous institutions being devalued in the face of federal and state agreements with companies, the uneven distribution between members of the community, and the great differences between worldviews, have a clear effect on the increase in the risk of violence. Here we are talking about building new dialogue mechanisms that are not attached to the principles of prior and informed consultation, for example. Or to cases where ejido authorities are retaken over the authorities of indigenous peoples, which may be different, and lose legitimacy within the same community. They are the imposed institutional orders that can facilitate the use of the remedy of violence either as a means of negotiation, or as an effect of inequality.

Institutions matter. At the beginning of this piece, we started with that premise. This phrase states that the rules of the game have an effect on the way in which violence governs lives: how conflicts are managed, how asymmetries of power are resolved, how different ways of life are brought into dialogue. Mining is one of the most contentious activities in which they occur. The origins can start from basic instincts for survival, from clashing worldviews or from manifestations of asymmetries of power between the parties. And in all of these cases, institutions matter.

Taking the example of the ejido, we understand how there are ways in which different institutions can exacerbate violence. Violence itself can be part of the rules of the game. Actors who defend different institutional orders can also compete with each other, so that their rules work. Finally, institutions, usually those of the State, can impose themselves on rules established in local communities. And, although these may be situations that not only talk about environmental governance, they are particularly important in situations where there are different worldviews about our relationship with the environment.

Returning to Yasnáya Aguilar, we are talking about Jëtsuk, or defense of the territory, where it is understood as an existential struggle of the Mixes communities of which she is part (2021). You can't talk about peace without talking about the environment, and vice versa. So, when we discuss whether institutions, or the rules of the game, matter to understand this relationship, of course they matter. They matter because, if we want to face the climate crisis fairly, we have to look for ways in which the rules of the game of the future and the present build peace, not violence.

CEMDA Report on the Situation of Environmental Human Rights Defenders

https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/conflicto/view/1002

https://elpais.com/mexico/2021-04-04/jetsuk-nuestro-ambientalismo-se-llama-defensa-del-territorio.html

http://miranoscemda.org.mx/#informe

Explore reflections, research and field learning from our work in ecosystem restoration.